Chinese Wallpaper in United Kingdom’s Most Exclusive Residences

Paper Route

- Text by J.H. White

“Chinese wallpaper is very much a living tradition,” says Emile de Bruijn, senior collections management registrar at UK’s National Trust. It’s an art form that has a surprising heritage—“a global phenomenon that is both Chinese and Western.”

Oriental Arts Earn An Adoration Of Europeans

As sea routes from Portugal, Spain, England, and the Netherlands began to open up to Asia in the 16th century, Europeans quickly acquired a taste, and adoration, for oriental products. Silk, porcelain, lacquer, and Chinese wallpaper were among these “amazing high-tech luxury goods,” he says.

Chinese wallpaper was a global product—made by Chinese artisans, adapted to a new form for Europeans. Historically, the Chinese would decorate their mansions by hanging beautiful paintings of birds, flowers, and landscape scenery on the walls. Europeans wanted these exotic scenes to be painted directly on the walls themselves, so Chinese wallpaper was born.

The wallpaper illustrated deeper Chinese philosophies, such as virtues of Confucian society. One that’s “inspired high above, showing all the different classes, [with] each [person] having a role in society, working and living harmoniously,” de Bruijn says.

Join us on a tour as we explore five of the most exquisite, historic examples of Chinese wallpaper still taking people’s breath away in the UK today.

Harewood House

In West Yorkshire, England, Harewood House was built in the mid-18th century. At Harewood House, renowned furniture-maker Thomas Chippendale acted as a “wonderful example of an 18th-century interior design service,” de Bruijn says. Chippendale supplied the Chinese wallpaper, silk, kitchen equipment—a chopping block, for example—and, of course, the furniture.

The Chinese wallpaper depicted harmonious scenes of Confucian society, where workers of all social classes work seamlessly together. Chippendale blended the Oriental wall art with green and gold imitation lacquer furniture that he designed.

“It’s a great example of how genuine Chinese products were combined with imitation Asian products made in Britain,” de Bruijn says.

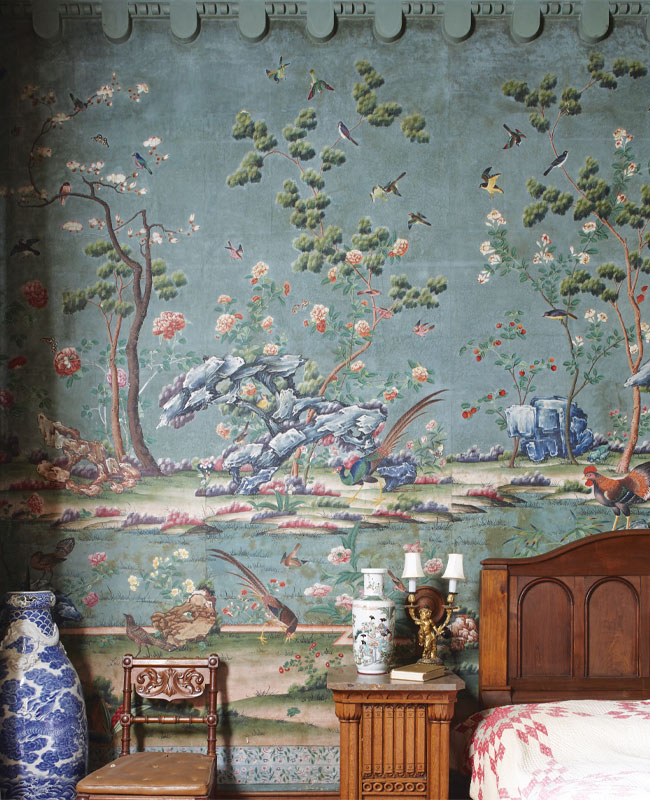

Penrhyn Castle

In the 1830s, Penrhyn Castle, located in northern Wales, was designed and built in the Neo-Medieval style.

Thomas Hopper, a favourite architect of King George IV, designed the house and its furniture. He included three rooms with Chinese wallpaper. “Why would you want to have a Chinese element in a medieval castle? That shows how much Chinese wallpaper was now part of the expected high-end British interior,” de Bruijn says.

The Lower India Room, for example, depicts a beautiful Chinese garden with a scholar’s rock, pond, flowering trees and plants, birds, and butterflies—a landscape that transports you away to the mysterious world of China.

Saltram House

Saltram House is a King George II era mansion, situated in Devon, in South West England. It was deemed by architectural critics to be “the most impressive country house in Devon.”

It showcases a collage of Chinese prints, essentially the precursor to Chinese wallpaper. Prints would be purchased and then harmoniously blended together on the wall.

“A lot of these prints don’t exist anymore in China, and only really exist on the walls of some historic houses in Europe, such as Saltram,” de Bruijn says.

Although the owners of Saltram probably were unaware at the time of purchase, these woodblock prints tell some of China’s most famous legends: there are scenes from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, one of China’s four great classic novels, along with spiritual landscapes depicting Taoist immortals.

Belton House

Built by Sir John Brownlow, 3rd Baronet, in the mid-17th century, Belton House is a National Trust property in Lincolnshire, a county in eastern England.

The Chinese bedroom inside the Belton House is adorned with walls alive with whimsy and meaning. The wallpaper depicts large bamboo stalks that reach all the way to the ceiling. The people on the ground are smaller scale than the bamboo, making it unrealistic but figurative. Bamboo is a symbol of uprightness, so its increased size could suggest the righteousness of the Confucian society. Meanwhile, people are happily interacting with each other on the ground, trading goods and playing checkers, among other activities.

“These exotic elements almost became domesticated in the British and wider European interiors,” he says. “By the time of this room at Belton, which was done in 1840, this Chinese element had become part of British high-end taste.”

Erddig House

The Erddig House is located in Wales, in Northeastern England, built in the mid-17th century for Josiah Edisbury, the High Sheriff of Denbighshire.

The Picture Room at the Erddig House showcases a subcategory of Chinese wallpaper. Chinese painting workshops began producing ready-made sets of 12 to 20 painted prints that could be installed individually or together in a huge panoramic scene. The Picture Room portrays Chinese landscapes with scenes of rice cultivation and silk production.

“[The Chinese wallpaper] was almost like windows,” de Bruijn says. This 17th-century trend developed concurrently with the development of the natural, asymmetrical English landscape garden. “On the one hand, if you looked out of the real window, you could see a naturalistic landscape garden. Then, of course, on your wall you had Chinese landscapes.”

Inspired for a Beautiful Life

Related Articles

Step Inside an Artful Modern Farmhouse

How interior designer Reineke Antvelink has transformed a traditional farmhouse into a stylish residence.

Michael Kors on the Art of Gift-Giving

“The best gifts walk the line between glamorous and practical”